D

Deleted member 1486

Guest

Link: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/...-felt-alone-i-tried-to-take-my-life-fz3pd280r

As Alan Quinn rolled the ball to Christian Nadé — 45 yards out, back to goal, Kolo Touré breathing down his neck — the Sheffield United striker knew exactly what he was going to do. A few blistering seconds and one deft touch later, the ball nestled in the back of Arsenal’s net.

Bramall Lane, December 30, 2006: the last time Sheffield United and Arsenal, who return to Yorkshire tonight, met in the Premier League and Nadé, the only goalscorer in Sheffield United’s first win against the London club in 33 years, recalls every moment in vivid detail.

“A few minutes earlier, I was in the same position against Kolo Touré and he anticipated to go in front of me, but I managed to control and turn with the ball,” Nadé says. “So I thought, ‘OK, he knows what I’m going to do, so I need to do something different.’ When I was younger my brother used to score goals like that all the time — just leave the ball, and run. When I saw the ball coming, I knew I would beat him in a race.”

As Nadé spun away and shrugged off the overeager Arsenal defender he saw Jens Lehmann, the goalkeeper, rushing off his line. “I thought, ‘What is he doing, is he crazy?’ I knew I just had to lift the ball and I would score, and that’s what I did,” says Nadé of his first Premier League goal — and what a game. Lashings of rain, mud and thunder; a second-half set-to between Neil Warnock and Arsène Wenger; and Phil Jagielka, the 21-year-old defender, donning the gloves of the injury-stricken goalkeeper, Paddy Kenny, to man the sticks, memorably denying Robin van Persie, during the final half-hour in a raucous atmosphere.

“The fans were behind us, and Warnock had this way of motivating his players,” Nadé says. “I don’t know how he did it — he’s still doing it — but he has got this way of talking to you to make you feel like you are the best player in the world. Every time I was on the pitch, I would do everything I could to make him feel proud of me.”

Nadé, a shy 22-year-old who could barely speak a word of English, had arrived from Troyes, the Ligue 1 club, in the summer of 2006. Who could have known that that moment in front of the Saturday night Sky Sports cameras would be the pinnacle of his career? There would be just two more Premier League goals for Nadé, in defeats against Reading and Newcastle United, as United were cruelly, and controversially, relegated on the final day of the season, while West Ham United survived.

Nadé, in the summer of 2007, was deemed surplus to requirements by Warnock’s replacement, Bryan Robson, and the 35-year-old, who now plays for Annan Athletic, the Scottish League Two club, has since endured an itinerant and chaotic existence, which has tested his love of football, his wellbeing, and very nearly had tragic consequences.

Not long after Nadé joined Heart of Midlothian, in August 2007, hopes of a reunion with Warnock at Crystal Palace were dashed by the Edinburgh club when they rejected an offer for him. Nadé’s dearth of goals at Tynecastle was compounded with issues about his weight and a lack of professionalism, which led Csaba Laszlo, the former Hearts manager, to label Nadé the “fat student”.

Hearts reneged on the offer of a contract extension after a dressing-room bust-up with Ian Black, the midfielder, and so Nadé joined the Cypriot club Alki Larnaca, where, after six months, his wages failed to materialise. As agents arranged trials in South Africa, Vietnam and then Thailand, life off the pitch became increasingly erratic. One night in Pretoria, Nadé says, he was the passenger in a friend’s car when suddenly a vehicle screeched to a halt blocking the road in front of them. “I said, ‘Wow, turn back.’ But he opened the glove box, and he pulled out a gun,” Nadé says. “They say in South Africa after 8 o’clock you don’t even stop for red lights. We managed to get away, but I said, ‘I want to go home.’ ”

After more fruitless trials in Vietnam, where he lived on bread and tuna for months, and in Thailand, Nadé almost quit football altogether. Samut Songkhram finally offered him a two-year contract in 2011, during which time he lived in Bangkok with four African players and squeezed into a rickety little bus to travel the three-hour round trip to and from training every day. But often there was little choice. “To get a taxi to stop for four or five black guys in Bangkok, sometimes you stood on the side of the road for half an hour — and there were a lot of taxis, ” he says.

“Whenever I scored, my team-mates wouldn’t come and celebrate with me. Most of the other players earned about 20,000 Baht [about £500] a month; I was earning a few hundred thousand Baht. We trained on half a pitch, and on the other half some villagers would be playing five-a-side. And in raining season, the ball didn’t bounce, just splashed water.”

Outdoor showers, with fans peering through holes in the wall, lizards scuttling around his feet, and a curtain of mosquitoes also took some getting used to. “My young brother Kevin came to watch training one day, and he said to me, ‘You are really strong. I came to see you play against Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, and now I see you here — I feel bad for you. But you’re one of the strongest people I know.’ That made me sad, but it gave me strength too.”

A knee injury requiring surgery took Nadé back to Scotland, and soon Dundee, in 2014, where promotion from the Scottish Championship followed. Annan, for whom Nadé has scored three goals in eight League Two appearances this season, are Nadé’s 14th club in all and his seventh in the past five years.

More than an hour in the company of Nadé — who is warm, engaging and good humoured — is enough to make clear, however, that life as a footballer has been both a blessing and a curse. “I left my family when I was 12, a wee boy, to go to a French academy,” Nadé, who grew up on the outskirts of Paris with his five brothers and sister, says. “Then when I was 16, I went to Troyes, and never came back. Even when I was going home I felt like a stranger. They would laugh at things I didn’t understand, do things when I couldn’t be there. I realised, ‘I’m on my own.’ Everything built up, and built up over the years. And that’s when I tried to take my life.”

In 2014, while a Raith Rovers player, Nadé went to a beach near his home early one day, sent messages to his family, telling them that he was sorry and that he loved them, then left his phone on the beach and walked in to the sea. The water was up to his neck when he heard a voice calling: a friend who had been alerted by his brother and who had called the police and an ambulance. “At first I felt ashamed,” Nadé says. “At training, I always acted like one of the happiest in the team. But as soon as I went home, I felt I was alone.”

Nadé, who had depression diagnosed, has been working with Back Onside, a Scottish peer-to-peer mental health charity which works in confidence with players and clubs throughout the SPFL, for the past six months. “I realised I need to put myself out there, and talk, help other people suffering with, or going towards, depression,” he says.

“I was talking in a school and they asked me if I would change anything. I said millions of children want to be football players, and I was one of the lucky ones who managed to live the dream. So I don’t regret being a footballer, or having been where I’ve been. But if I had the choice to be a doctor tomorrow instead, I would.”

It has been quite a journey for the fresh-faced forward who, after that moment of magic at Bramall Lane 13 years ago, wheeled off in celebration and punched the sky with glee. “I love Pelé and when he used to score, he would punch the sky,” Nadé says. “I always said if one day I score in the Premiership, that’s the way I would celebrate. He is the only player who, if I met, I would cry. He encapsulates everything I love about football. That was like saying thank you for making me fall in love with this game.”

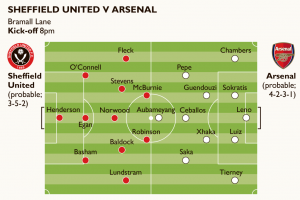

HOW THEY LINED UP

Sheffield United 1-0 Arsenal

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Sheffield United (4-4-2): P Kenny (sub: M Tonge 61min) — C Armstrong, R Kozluk, C Morgan, P Jagielka — M Leigertwood (sub: C Davis 27), K Gillespie, N Montgomery, A Quinn — C Kazim-Richards, C Nadé (R Hulse 70).

Arsenal (4-4-2): J Lehmann — J Hoyte (sub: F Fàbregas 64), P Senderos, K Touré, G Clichy — M Flamini, J Baptista, T Rosicky (sub: Denilson 83), Gilberto Silva — J Aliadière, R van Persie.

Referee Lee Mason.

As Alan Quinn rolled the ball to Christian Nadé — 45 yards out, back to goal, Kolo Touré breathing down his neck — the Sheffield United striker knew exactly what he was going to do. A few blistering seconds and one deft touch later, the ball nestled in the back of Arsenal’s net.

Bramall Lane, December 30, 2006: the last time Sheffield United and Arsenal, who return to Yorkshire tonight, met in the Premier League and Nadé, the only goalscorer in Sheffield United’s first win against the London club in 33 years, recalls every moment in vivid detail.

“A few minutes earlier, I was in the same position against Kolo Touré and he anticipated to go in front of me, but I managed to control and turn with the ball,” Nadé says. “So I thought, ‘OK, he knows what I’m going to do, so I need to do something different.’ When I was younger my brother used to score goals like that all the time — just leave the ball, and run. When I saw the ball coming, I knew I would beat him in a race.”

As Nadé spun away and shrugged off the overeager Arsenal defender he saw Jens Lehmann, the goalkeeper, rushing off his line. “I thought, ‘What is he doing, is he crazy?’ I knew I just had to lift the ball and I would score, and that’s what I did,” says Nadé of his first Premier League goal — and what a game. Lashings of rain, mud and thunder; a second-half set-to between Neil Warnock and Arsène Wenger; and Phil Jagielka, the 21-year-old defender, donning the gloves of the injury-stricken goalkeeper, Paddy Kenny, to man the sticks, memorably denying Robin van Persie, during the final half-hour in a raucous atmosphere.

“The fans were behind us, and Warnock had this way of motivating his players,” Nadé says. “I don’t know how he did it — he’s still doing it — but he has got this way of talking to you to make you feel like you are the best player in the world. Every time I was on the pitch, I would do everything I could to make him feel proud of me.”

Nadé, a shy 22-year-old who could barely speak a word of English, had arrived from Troyes, the Ligue 1 club, in the summer of 2006. Who could have known that that moment in front of the Saturday night Sky Sports cameras would be the pinnacle of his career? There would be just two more Premier League goals for Nadé, in defeats against Reading and Newcastle United, as United were cruelly, and controversially, relegated on the final day of the season, while West Ham United survived.

Nadé, in the summer of 2007, was deemed surplus to requirements by Warnock’s replacement, Bryan Robson, and the 35-year-old, who now plays for Annan Athletic, the Scottish League Two club, has since endured an itinerant and chaotic existence, which has tested his love of football, his wellbeing, and very nearly had tragic consequences.

Not long after Nadé joined Heart of Midlothian, in August 2007, hopes of a reunion with Warnock at Crystal Palace were dashed by the Edinburgh club when they rejected an offer for him. Nadé’s dearth of goals at Tynecastle was compounded with issues about his weight and a lack of professionalism, which led Csaba Laszlo, the former Hearts manager, to label Nadé the “fat student”.

Hearts reneged on the offer of a contract extension after a dressing-room bust-up with Ian Black, the midfielder, and so Nadé joined the Cypriot club Alki Larnaca, where, after six months, his wages failed to materialise. As agents arranged trials in South Africa, Vietnam and then Thailand, life off the pitch became increasingly erratic. One night in Pretoria, Nadé says, he was the passenger in a friend’s car when suddenly a vehicle screeched to a halt blocking the road in front of them. “I said, ‘Wow, turn back.’ But he opened the glove box, and he pulled out a gun,” Nadé says. “They say in South Africa after 8 o’clock you don’t even stop for red lights. We managed to get away, but I said, ‘I want to go home.’ ”

After more fruitless trials in Vietnam, where he lived on bread and tuna for months, and in Thailand, Nadé almost quit football altogether. Samut Songkhram finally offered him a two-year contract in 2011, during which time he lived in Bangkok with four African players and squeezed into a rickety little bus to travel the three-hour round trip to and from training every day. But often there was little choice. “To get a taxi to stop for four or five black guys in Bangkok, sometimes you stood on the side of the road for half an hour — and there were a lot of taxis, ” he says.

“Whenever I scored, my team-mates wouldn’t come and celebrate with me. Most of the other players earned about 20,000 Baht [about £500] a month; I was earning a few hundred thousand Baht. We trained on half a pitch, and on the other half some villagers would be playing five-a-side. And in raining season, the ball didn’t bounce, just splashed water.”

Outdoor showers, with fans peering through holes in the wall, lizards scuttling around his feet, and a curtain of mosquitoes also took some getting used to. “My young brother Kevin came to watch training one day, and he said to me, ‘You are really strong. I came to see you play against Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, and now I see you here — I feel bad for you. But you’re one of the strongest people I know.’ That made me sad, but it gave me strength too.”

A knee injury requiring surgery took Nadé back to Scotland, and soon Dundee, in 2014, where promotion from the Scottish Championship followed. Annan, for whom Nadé has scored three goals in eight League Two appearances this season, are Nadé’s 14th club in all and his seventh in the past five years.

More than an hour in the company of Nadé — who is warm, engaging and good humoured — is enough to make clear, however, that life as a footballer has been both a blessing and a curse. “I left my family when I was 12, a wee boy, to go to a French academy,” Nadé, who grew up on the outskirts of Paris with his five brothers and sister, says. “Then when I was 16, I went to Troyes, and never came back. Even when I was going home I felt like a stranger. They would laugh at things I didn’t understand, do things when I couldn’t be there. I realised, ‘I’m on my own.’ Everything built up, and built up over the years. And that’s when I tried to take my life.”

In 2014, while a Raith Rovers player, Nadé went to a beach near his home early one day, sent messages to his family, telling them that he was sorry and that he loved them, then left his phone on the beach and walked in to the sea. The water was up to his neck when he heard a voice calling: a friend who had been alerted by his brother and who had called the police and an ambulance. “At first I felt ashamed,” Nadé says. “At training, I always acted like one of the happiest in the team. But as soon as I went home, I felt I was alone.”

Nadé, who had depression diagnosed, has been working with Back Onside, a Scottish peer-to-peer mental health charity which works in confidence with players and clubs throughout the SPFL, for the past six months. “I realised I need to put myself out there, and talk, help other people suffering with, or going towards, depression,” he says.

“I was talking in a school and they asked me if I would change anything. I said millions of children want to be football players, and I was one of the lucky ones who managed to live the dream. So I don’t regret being a footballer, or having been where I’ve been. But if I had the choice to be a doctor tomorrow instead, I would.”

It has been quite a journey for the fresh-faced forward who, after that moment of magic at Bramall Lane 13 years ago, wheeled off in celebration and punched the sky with glee. “I love Pelé and when he used to score, he would punch the sky,” Nadé says. “I always said if one day I score in the Premiership, that’s the way I would celebrate. He is the only player who, if I met, I would cry. He encapsulates everything I love about football. That was like saying thank you for making me fall in love with this game.”

HOW THEY LINED UP

Sheffield United 1-0 Arsenal

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Sheffield United (4-4-2): P Kenny (sub: M Tonge 61min) — C Armstrong, R Kozluk, C Morgan, P Jagielka — M Leigertwood (sub: C Davis 27), K Gillespie, N Montgomery, A Quinn — C Kazim-Richards, C Nadé (R Hulse 70).

Arsenal (4-4-2): J Lehmann — J Hoyte (sub: F Fàbregas 64), P Senderos, K Touré, G Clichy — M Flamini, J Baptista, T Rosicky (sub: Denilson 83), Gilberto Silva — J Aliadière, R van Persie.

Referee Lee Mason.